Stress is the response of an animal’s body to a stimulus. This stimulus is not always negative. However, when it is associated with a negative situation, a decrease in performance and productivity is inevitable because the animal’s health is affected, especially early in their lives.

At birth, piglets are neurodevelopment but physiologically immature. In terms of nutritional reserves, they are born with only 1-2% of fat, which is mainly structural. In the first hours of their life, these animals are totally dependent on the catabolic glucose of hepatic glycogen as their main source of energy.

From birth, piglets have many stressors early in life. The level of hepatic glycogen at birth is only sufficient to meet the energy requirements for 15-20 hours after birth. In the absence of artificial heating, piglets, especially those that are not breastfed, become hypoglycemic and seek the warmth of their mothers. As a result, they are often crushed. Therefore, deliveries should accompany them whenever possible. In addition, some postpartum care should be taken to ensure the survival and health of the bedding, such as proper temperature, proper belly button disinfection, preventive medication, etc.

Weaning is another complicated period for piglets. Stress factors mainly involve a new environment, new social interactions, and dietary changes. The consequences of this stress can lead to substantial production losses. Commercial weaning occurs between 17 and 28 days of age when the piglet’s immune system is still immature and its circulating antibodies are at their lowest level (around 28 days of age). This period is called the “immune gap” oder “post-weaning gap” because the piglet’s acquired immune system is not fully developed and is, therefore, more susceptible to intestinal problems. After that, antibody levels gradually increase as the animal develops natural immunity.

At birth, piglets passively receive antibodies from their mothers through the intake of colostrum. The absorption of antibodies depends on the absorption capacity of the intestinal epithelium and begins to decline 24-36 hours after birth. This means that the environment, nutrition, health, and general condition of the sow will directly affect the newborn and weaned piglets, as their development directly affects their colostrum and milk during pregnancy, and postpartum body contact (microbiota transmission) and lactation. It is important to remember that the longer the time between birth and first breastfeeding, the greater the chance of infection.

Colostrum contains high levels of total solids and protein but is low in fat and lactose. It also contains high levels of immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, and IgM) and the concentration decreases over time with breastfeeding. Colostrum and milk also contain a number of other immune system cells, including neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, and mammary epithelial cells, as well as leukocytes that stimulate the development of cellular immunity in newborns. It is easy to understand that the health status of the sow will directly affect the spread of passive immunity to the piglets.

The piglets have certain limitations in their digestive system, such as insufficient enzyme secretion, hydrochloric acid, bicarbonate, and mucus, which can interfere with the adequate digestion and absorption of nutrients. The stress of switching from milk (highly digestible) to solid food (more complex and less digestible) may result in reduced food and water intake. Approximately 50% of weaned piglets finish their feeds within 24 hours of weaning, and 10% start feeding 48 hours after weaning.

When the digestibility of the diet is low (which is usually related to the quality of the ingredients), pathogenic bacteria proliferate. These bacteria use these ingredients as substrates to multiply, leading to intestinal problems such as diarrhea, which can lead to a significant reduction in early performance and high mortality. Thus, during the 7 to 14 days after weaning, the composition of the intestinal microbiota changes significantly, generating competitive resistance or rejection.

On the market, we can find natural additives that can provide compounds that stimulate the body to respond more effectively to stressful stimuli imposed in the field. Although nucleotides are not considered essential nutrients, these additives play an important role in various metabolic processes, especially in body tissues and in energy production due to high cell proliferation during the life stages of animals that require large amounts of supplementation.

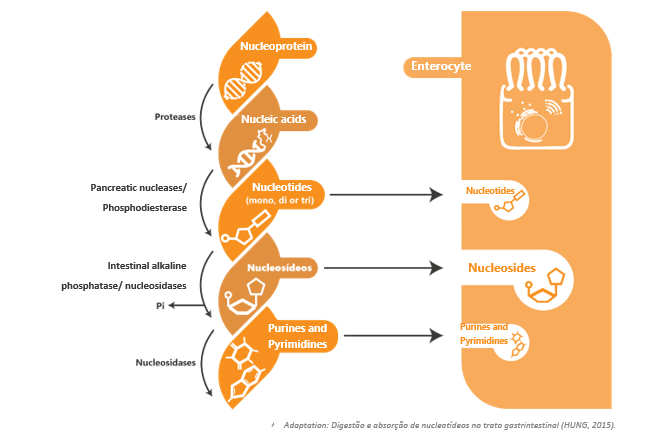

Enterocytes can readily absorb free nucleotides and nucleosides from the intestine. They are particularly important for rapidly proliferating tissues and limited ability to synthesize from the ab initio pathway (the primary nucleotide production pathway), such as intestinal epithelial cells, blood cells, hepatocytes, and immune system cells (Figure 1). When the body can synthesize less energy-consuming nucleotides, they are used by the recycling pathway, as it recycles bases and nucleotides degraded by dead cells or dietary nucleic acid metabolism. However, when endogenous supply is insufficient, nucleotides from exogenous sources become semi-essential or “conditionally essential” nutrients. This occurs mainly in animals undergoing rapid growth (early stages), reproduction, stress and challenge stages.

Ensuring proper management, nutrition and health programs during pregnancy, farrowing, postpartum and weaning is an important way to ensure good piglet performance, as mitigating stressors will determine the balance between immunity and performance. Therefore, supplementing the diets of pregnant and lactating sows with natural additives to provide adequate support for piglets to better cope with challenges and stressful stimuli imposed by the field is essential to the feeding system. In addition to being a natural source of free nucleotides and nucleosides, which are extremely important for the high cell proliferation phase, Hiyeast® yeast hydrolysate also provides amino acids, peptides and short-chain peptides as well as glutamine, MOS and high levels of β-glucan, thus providing great benefits for the nutrition and health of the animal.